Mixing energy during cement mixing, what is it and why is it important? What can be done to control it?

First of all - what is mixing energy?

It is the energy used per mass unit of the cement slurry, mixing the mix-water with the dry cement (and possibly other) particles. Mixing energy is measured in KJ/kg. It is basically a function of the power in the mixing system and the time the slurry is exposed to it. Some mixing energy is required to achieve a homogeneous mix and the desired properties. Too much mixing energy can lead to various type of issues, some negative. To me, the key is that the mixing energy should be close enough to the mixing energy used in the lab so that the actual slurry you mix on the rig has similar properties to the one mixed and tested in the lab.

On a side note, very high mixing energy can have another obvious effect, in some cases with a dramatic result.The mixing energy increases the temperature in the slurry, not that much normally because from the time the slurry is mixed until it goes downhole is relatively short. However, in some cases (often when things are going sideways for other reasons), you may end up recirculating the same slurry for several minutes. If you then have a slurry designed for low temperature, you can have a flash setting in the tub (very unpleasant) or if not, possibly end up with a shorter thickening time than you expect, again possibly leading to very unpleasant results. Just be aware of this.

What are the effects of different amounts of mixing energy?

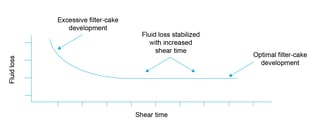

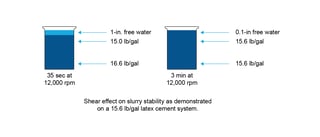

There were some papers written in the late 80s (SPE-15578, Orban et al. 1986, SPE-18895, Vidick, 1989) showing some of the variations in properties with different levels of mixing energy. There were apparent differences measured in viscosity, fluid loss, free water and thickening time. I believe these papers are well accepted in the industry although a few years later there was a paper showing that the same properties were not much affected by mixing energy, but rather somewhat by shear rate, hence the intensity level was more important than the total energy. Experts in competing companies wrote these papers, but if you dig into them a bit, they may not be as much in disagreement as it seems initially.

So, what does this mean?

The first thing to be aware of is that the mixing energy for the slurry in the lab is in almost all cases above or way above the energy the slurry gets in a field mixer. It will be very unusual that the field mixer exerts more energy than the lab mixer. The testing performed in the papers above shows in general that if you have mixing energy less than around ½ of the mixing energy you get in the lab, you will start having some effect on specific properties. Most significantly changes are:

- Higher viscosity (both Yield value and Plastic viscosity will increase)

- Longer thickening Times

- Higher fluid loss and free water values

I would say the concern for the effect this has on thickening time is low, a longer than expected TT will rarely create catastrophic results. The higher fluid loss combined with a larger viscosity can be problematic on critical jobs, for example liner jobs in reservoir sections. If you lose more fluid to the formation than you expect because of higher fluid loss AND higher viscosity, you will get even higher viscosity leading to even further fluid loss and you can have a runaway process that in worst case leads to a bridging-off in the annulus (see more on this in Fluid Loss in Cement Slurries for Oil Well Applications and Free Water in Cement Slurry: Why is it Critcal?).

In any case, you will get higher pump pressure and possibly a change in flow behavior leading to a less than optimum mud removal or displacement.

What to do?

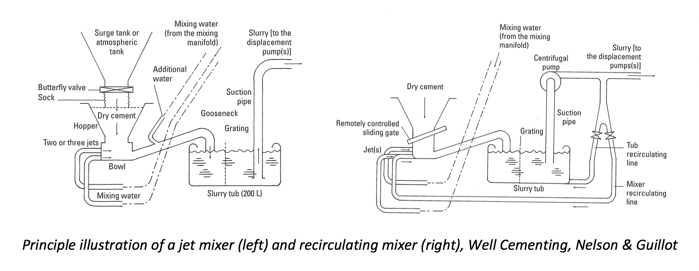

Various type of mixers will give different amount of mixing energy, but also how and what you mix matters. A recirculating mixer can be adjusted differently, which will affect the energy. If a diesel engine drives the circulating pumps, different rpm on the engine will change the amount of energy. Often there is a butterfly valve on the recirculating line that sometimes gets choked back a bit for various reasons (splashing etc.). If your downhole rate is low, the time for the slurry to recirculate and mix is longer. Hence you get more mixing energy per volume unit. In many cases, you can decide on a higher or lower downhole rate that will get you more or less mixing energy.

A typical old-fashioned jet mixer (without recirculation and a downhole rate of 4 bpm) gives around 1/5 of the mixing energy you get in the lab mixer. Compared to the jet mixer, a 6 bbl recirculation mixer produces about twice the energy, and a 25 bbl recirculation mixer will triple it. Now if your downhole rate doubles, the mixing energy theoretically goes down to half.

So basically, if you are using a recirculating mixer, there will be negligible difference between lab test results and the rig mix if your downhole rate is 4 bpm or less.

When doing the lab testing for the slurry, if you know or suspect issues related to mixing energy, you can modify the testing to some degree to consider less (or more) mixing energy during mixing. You need to be careful moving away from standard API testing parameter, but even though you may not be able to replicate the exact amount of different energy in the lab, you can do some tests decreasing or increasing the energy during mixing and at least get some idea of the sensitivity of the slurry to less (or additional) mixing energy for your specific slurry.

So, if you have a well working recirculating mixer, you should not have much problems reaching sufficient mixing energy, unless rates are very high. In that case, you may want to redesign the job with lower downhole rates. If you do not have a recirculating mixer and the job is critical, you may want to consider mixing the slurry in a batch mixer. Since most critical jobs are relatively small, this should be possible.

There is no magic solution to it, and you cannot control everything, but it is essential to be aware of this factor and the possible effects, then you can take it into account when planning the job.