Gas migration is a well-known phenomenon in oil and gas wells around the world. Probably because it is very common. You must know what it is and how it occurs.

This is an updated version of a previously published article, for the pleasure of our new readers.

Gas migration means that gas from somewhere in the well, enters the well and migrates to another place. This is usually not a good thing and can in some cases if unchecked, lead to a disaster. That was what happened outside the coast of Louisiana in April 2010.

The offshore oil rig Deepwater Horizon experienced gas migration after cementing – the explosion and fire killed 11 people and seriously injured another 16. The photo taken by the U.S. Coast Guard shows the rescue mission trying to save the lives of the Deepwater Horizons 126-person crew.

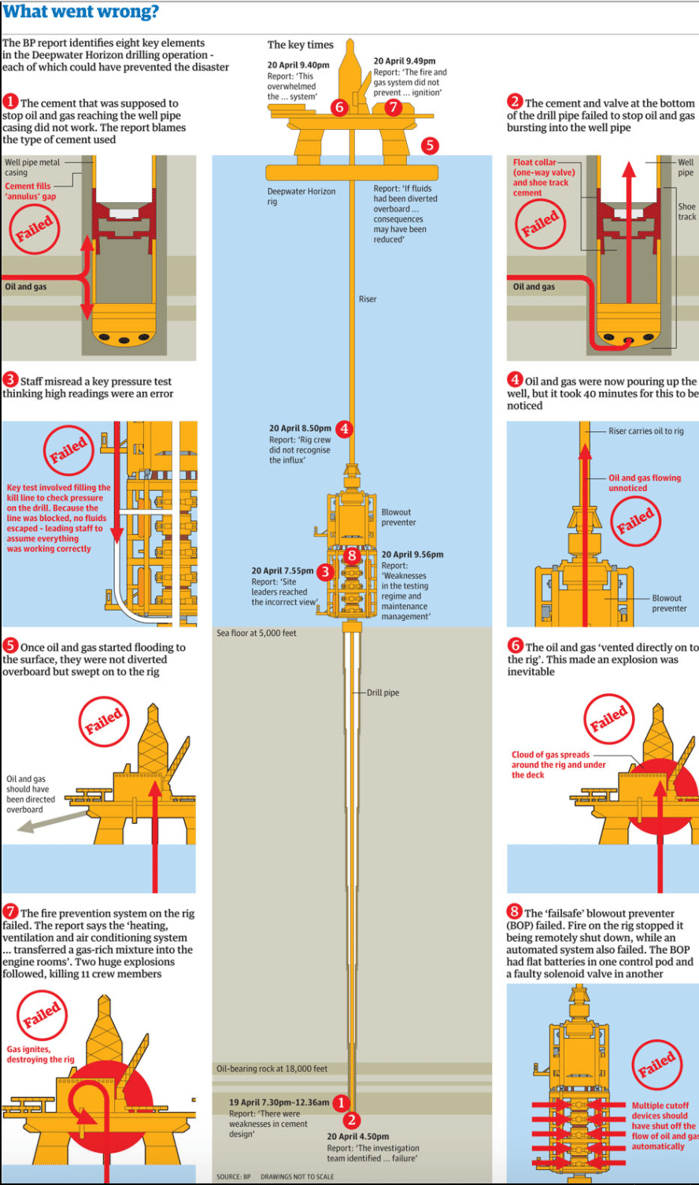

The report made after the accident identified several elements in the drilling and abandonment operation that went wrong and could have prevented the disaster.

Download free e-book: Guidelines for setting cement plugs.

One thing is when you see or experience gas migration, but more interesting is what the cause is and when it arose.

Deoilit.com published this infographic after the BP-report was done:

Read also our case on how to get rid of gas in the mud return.

Avoid blow out

Gas migration can happen in a well while drilling or cementing, hence if the hydrostatic pressure from the fluid column gets below the pore pressure in a permeable formation that is exposed and contains gas, you will get gas migrating into your well.

In these cases, detection is relatively easy and actions can be taken to increase the pressure and circulate out the gas. If you cannot circulate, things can get a lot trickier.

The problem is that if you just get a small amount of gas into your well downhole (maybe just from pulling pipe too fast and swabbing out a bit of gas), if not quickly recognized and rectified, the situation will rapidly worsen.

A small gas volume downhole will move upwards and increase in volume as the pressure decreases. It will then decrease the hydrostatic pressure downhole and potentially lead to more gas coming into the well. This cycle leads to ever-increasing gas inflow, and if nothing is done, you can end up with a blowout.

READ MORE: Dealing with micro-annuli in casing cement

Be aware

Gas migration is often a concern when designing cement jobs. Engineers should take the necessary steps to ensure gas is under control in three different but very specific stages of the cementing process:

- During placement (primary pressure control).

- Shortly after placement, when the cement slurry gels, but is not yet cured (Transition time).

- When the slurry cures and beyond (including the rest of the life of the well).

First, the cement job itself must be designed so that, at no time during placement, the downhole pressure drops below the pore pressure. This can be challenging at times if using an unweighted wash as a pre-flush for the cement if you are operating close to the pore pressure. Most cement job simulation programs will quickly identify this issue, and you can take precautions to avoid it.

Then, immediately after the slurry is in place, a greater challenge arises as the cement slurry enters the “transition time”.

During this period, the slurry starts to set up and lose the ability to fully transmit the hydrostatic pressure needed to keep the gas in place, while at the same time it is not yet hard and impermeable to gas.

If this time is long, gas can enter the slurry and migrate, possibly creating unwanted communication channels.

Finally, we have gas migration in cement after it has set up, something maybe experienced a few days after the cement job, or in some cases - several years later.

There are several possible explanations:

- Channels created by dry mud left in place due to poor mud removal. There are several underlying reasons for this (Poor casing stand-off, poor fluid design, Inadequate pumping schedule,

- Migration paths created by loss circulation problems.

- Mechanical damages to the set cement column caused by stresses associated to pressure changes, temperature changes, geomechanical forces, etc.

Even if the cement job and placement were perfect, you could create migration path if you displace the cement with a heavy fluid and later displace the well to a light one. Then the pipe will shrink a bit and possibly open a micro annulus that can allow gas to migrate.

Long-term problems

I know in some cases we created a micro annulus during logging (bond log) right after cementing. The well was pressurized to get a better reading and (probably) compressed the cement in some places at a critical time of setting. Hence, when the pressure was bled off again, a micro annulus was created and again a possible channel for gas.

Later in the life of the well, problems can arise if the cement is exposed to stress, either from temperature or pressure variations or mechanical shock from hardware running in and out of the hole. Cement also naturally shrinks a bit after setting and can crack up if exposed to sufficient stress and loose bond with the pipe and create migration pathways for gas.

Keep in mind that the major objective of primary cementing is to provide zonal isolation and prevent fluids moving from one zone to another zone. Without complete zonal isolation in the wellbore, the well may never reach its full producing potential.

If you'd like to dig deeper, you may download this free guide: