When is Sustained Casing Pressure (SCP) an issue, how do we characterize an SCP scenario, and what are the options to cure it? Operators in the Middle East have proactively worked to define a framework with which they will tackle these problems. I see no reason why this knowledge shouldn’t be relevant in other areas of the oil and gas producing world. In May 2018, I had the opportunity of attending the SPE workshop, Sustainability Through Smarter Well Integrity, held at the Jumeirah Ethihad Towers in Abu Dhabi. The event counted with the participation of all the renown national oil companies from GCC (The Gulf Cooperation Council) as well as some global players.

A few of the presentations caught my eye. After decades of poor cementing designs for casings across shallow aquifers (that are also typically drilled through and cemented with severe loss of circulation), the operators in the region are facing a lack of well integrity. This is due to the failure of the cementing sheet that was aimed to isolate the reservoirs behind those surface- or shallow intermediate casings while protecting them from the corrosion caused by shallow aquifers. Sustained pressure and the leak of water or hydrocarbons through those annuluses is the common phenomenon that they all addressed.

Read more: Why SCP may be a challenge, and the option you have.

However, this is neither new nor different in other places around the world. What really got me interested is that, despite having no pressure from legislation regulate this matter, the operators are making proactive attempts to contain the situation, defining the framework with which they will tackle these problems. A few of the presentations were trying to answer these basic questions:

- When is Sustained Casing Pressure (SCP) an issue? (based on which standards, evaluation methods, etc.)

- How do we assess it / characterize it?

- How do we plan the treatment, based on the standards/rules? What is the length of an appropriate barrier? Do we get to the source of the leak?

- How do we test it afterward, and what is the basis for the tests?

So, I thought it would be a good idea to bring to the blog a series of articles discussing the answers to these questions.

The series will rotate around three main subjects:

- When is SCP an issue? (this article)

- How do we characterize an SCP scenario?

- What are the options to cure it, and how do we measure success?

Today, we will focus on the first question: When is sustained casing pressure an issue?

For this article, I decided to interview Mr. Andrey Yugay, Well Integrity Specialist for the ADNOC Onshore Technical Center, Integrity and Operational Excellence Division. Mr. Yugay was a session co-chair in the event above. He presented a paper addressing the protocol under which the well integrity team defines when a well becomes a liability in terms of zonal isolation and should be handled to the drilling and workover department for intervention. It also defined specific testing parameters to accept such a well back into production.

Here is what Mr. Yugay told us.

“Sustained casing pressure is evidence of failure in one of the well barrier elements. Once the sustained pressure is confirmed, the well is not in compliance with most companies' barrier policies. What to do then? You can kill and secure the well immediately, or you can evaluate the risks and allow the well to operate for a limited period under close surveillance until you get a chance to restore barrier integrity. The issue then is how to identify this window in which it is safe to keep the well flowing.

The answer to this question varies from place to place as legislation, operator’s standards and environmental conditions all play a role in this matter. However, the ultimate goal of well integrity is to prevent well control situations (uncontrolled release of hydrocarbons to surface). It all comes down to us establishing what stops the SCP wells from further barrier failure that leads to a well control situation; this is mostly about the integrity of the secondary barrier containing the leak and the severity of the leak itself”.

Read more: Sustained Casing Pressure (SCP): Defining if a scenario needs intervention

Andrey explains this point further:

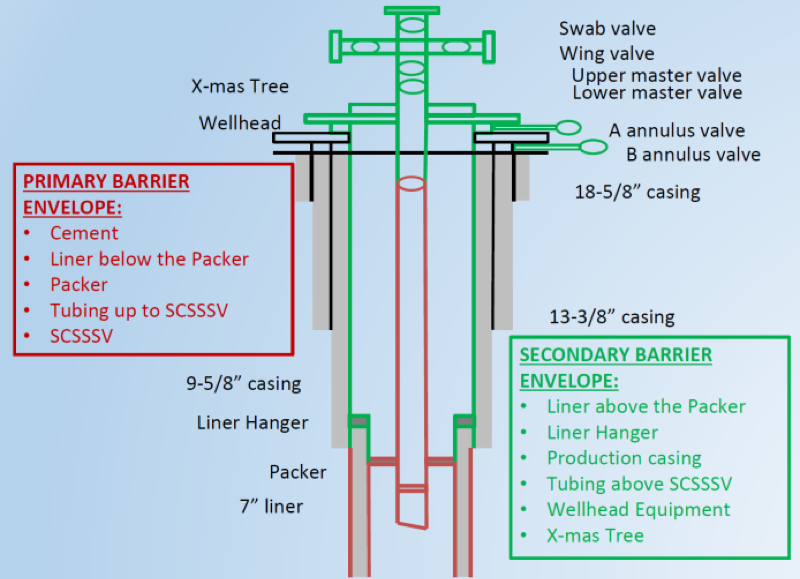

“In the double barrier envelope concept (See Figure 1), a well with SCP suffers of ‘primary barrier envelope’ failure. But the ‘secondary barrier envelope’ remains in place preventing a leak to the surface. Those secondary barrier envelope elements are usually wellhead equipment and outer casings that still contain the pressure. But, for how long?

With wellhead valves it is more or less clear – as long as you keep your preventive valve maintenance on, all should be fine. Worst case, you can install a valve removal plug (VR plug) and replace/repair the valve.

And the casing? Well, corrosion is an issue that can't be neglected in most of the fields. Relatively recently developed technology allows measurement of metal loss of the outer casings while running logging tool inside the production tubing. The method can't establish a precise minimum wall thickness of the pipes, but it can indicate that a pipe is corroded and susceptible to failure.

In both cases, defining a maximum allowable operating pressure for the annulus, and monitoring it, is the key for making the right decisions."

Figure 1. Well barrier envelope (WBE) concept.

Then Andrey talks about the severity of the leak:

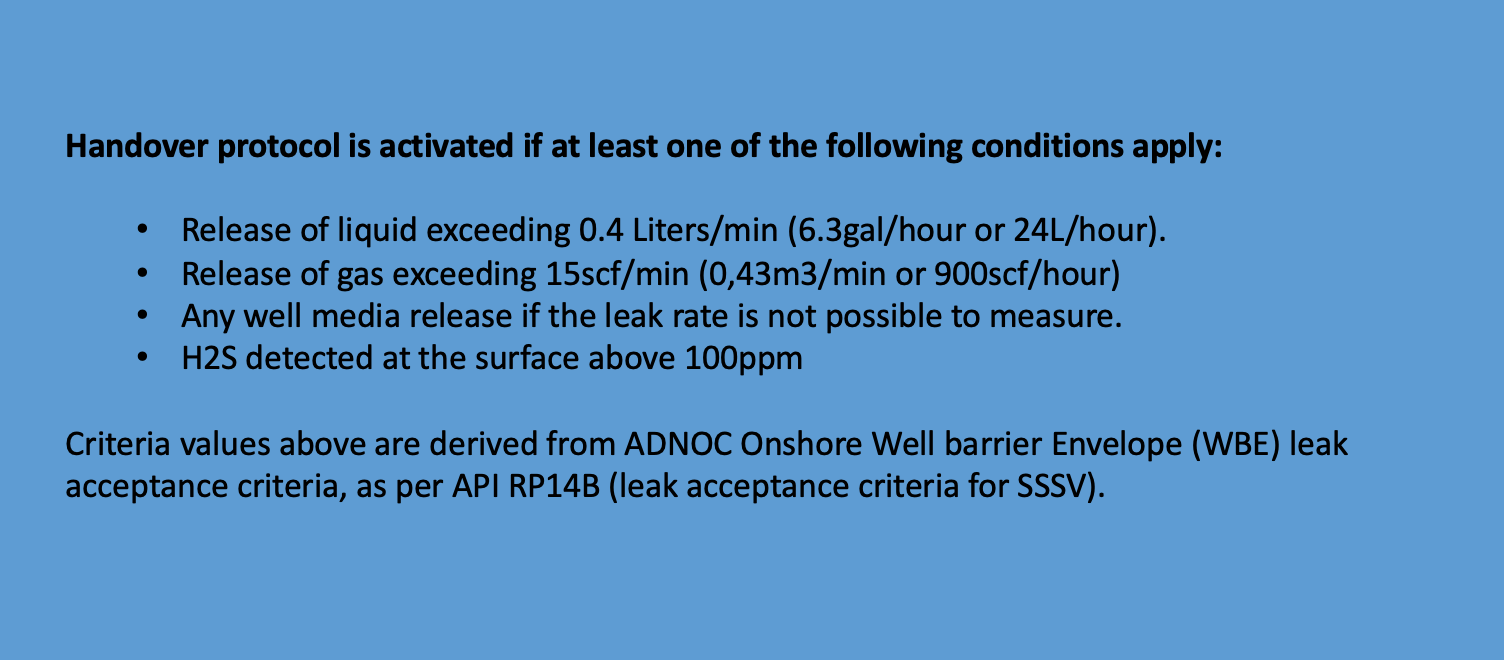

“The nature of the leak and the leak rate are the two main things to watch. Obviously, in a situation where H2S is detected during the bleed-off at concentrations above the defined company limit, (in ADNOC Onshore the critical threshold is 100 ppm of H2S) that would be more than enough to raise the alarm and direct the team to intervene the well immediately.

But where H2S is not an issue, we need to look at the severity of the leak itself. If it takes a few minutes (and small volumes) to bleed off the annuli pressure to zero, and a build-up to the original pressure takes several days or weeks -even in case of a secondary barrier failure- the overall business impact will be negligible and can be handled in a certain way.

Even if there is no H2S, but the scenario is a continuous non-bleedable pressure in the annulus, the severity of the risk here is greater due to increased complexity of the barrier restoration. How big the leak should be to allocate full company resources we normally refer to API RP14B, which regulates leak acceptance criteria for sub-surface safety valves. Some operators accept this valve as one of the well barrier envelope elements even though it has a defined acceptable leak rate, equivalent to around a bucket of liquid per hour."

It is worth mentioning that most operators in the region have implemented similar approaches as those described by Andrey.

One in particular (Saudi Aramco) went further: Before any workover operation in wells that goes through H2S bearing reservoirs, all casing-casing annuluses have to withstand a 500 psi positive pressure test before workover intervention begins. If the test fails, regardless of the presence of pressure in the annuli involved, treatment is done to ensure annulus integrity to, at least, 500 psi.

Figure 2. ADNOC Well Emergency Handover Protocol as presented at the SPE Workshop in May 2018.

Figure 2. ADNOC Well Emergency Handover Protocol as presented at the SPE Workshop in May 2018.

Prescriptive legislation dictating how to deal with the integrity loss that a sustained casing pressure scenario represents lacks in the region. To define the criteria for when to intervene in SCP scenarios, we see that all operators and service companies involved in dealing with sustained casing pressure in these countries refer to the standards from known industry hubs, such as the Gulf of Mexico (i.e., API) or the North Sea (i.e., NORSOK/OGN).

Sustained casing pressure has received increased international attention in both areas over the last few years. In 2006 the API developed the API-90 "Annular Casing Pressure Management for Offshore Wells." It was modeled after wells in the outer continental shelf (OCS) of the Gulf of Mexico, but applicable to the similar type of wells worldwide.

Read more: Why SCP may be a challenge, and the option you have.

Then, in 2008, the Norwegian Oil and Gas Association developed the Guidelines for Well Integrity No 117 (OGN 117), which includes a chapter in SCP modeled on wells from the Norwegian continental shelf.

The latest guideline in the matter was published in 2016 by the API. The recommended practice 90-2 "Annular Casing Pressure Management for Onshore Wells" constitute the agency's attempt to extend the best practices, procedures, and lessons learned from the API-90 to all wells in the U.S.

In its 6th revision, page 47, The Norwegian O&G association OGN 117 defines sustained casing pressure as “pressure in any well annulus that is measurable at the wellhead and rebuilds when bled down, not caused solely by temperature fluctuations or imposed by the operator."

But, as mentioned by Andrey, this doesn't mean the well needs to be killed or put out of service.

Following what is described in the guideline, and from what we see operators do in the North Sea, the Middle East, North Africa, and Australia, SCP is an issue when we believe it could escalate to an unmanageable situation with unacceptable consequences.

In part two of this article, I discuss four aspects of well annulus behavior and suggest how to interpret them to define whether you have an SCP scenario that needs intervention or not.

Additional reading: Download this free eBook to explore guidelines for setting cement plugs.